Road Conditions

It was not until after the first World War that local roads were surfaced with a compressed layer of small stones bound together with tar or asphalt – the MacAdam process (after its inventor John MacAdam 1756-1836). Previously the roads required constant maintenance throughout all seasons of the year.

George Young (1899-1987) a lifelong villager describes how the road was repaired early in the 20th century in this clip from an interview recorded in 1974

The constant job of filling the holes and dealing with the mud in winter and the dust in summer was also recalled by Dr R. Fisher.

'The road through the village has remained much the same as long as I can recollect. It has been made more level; the west side has been cut down and the east side a little raised. The green verge has been cut back a little. But the surface is very different : in the 1880s the repair was done with broken flints. In winter the roadmen scraped off the mud with large iron scrapers and in summer the dust blew along in clouds as high as the roofs of the smaller houses, and sometimes walked down the street in tiny whirlwinds. Outside the village on wider parts of the road verges were piles of flints, mostly collected off the fields, and old men with long handled hammers and goggles (if they obeyed orders) cracked up the flints to macadam size and piled the broken stones in neat heaps for the road surveyor to measure. Then in the autumn the flints were spread about three inches thick on the parts of the road needing repair and left for the traffic to roll in. There was no roller then. Things were very much the same up to the early 1900s. Mr. Bruce Beaton gave us a water cart and some of us experimented with calcium chloride with the idea that this would keep the surface constantly damp. It did not work.

Of course, the traffic was very small. The largest single item was probably the hay and straw carts going up to London. Another fairly heavy traffic was timber carting, mostly on carts with two large wheels, very long shafts, and a windlass to swing the tree trunks between the wheels. Bicycles began to be numerous in the late 1880's. Both the ' ordinary' (high bicycle) and the 'safety.' The 'safety' did not really win till pneumatic tyres came in. There used to be quite an excitement over club runs and races.'

Source: The History of Kings Langley Ed L.M.Munby KL WEA 1963 Appendix 10 p.156

This close up of part of Miss Gulstan's class probably 1902/3 shows the children's footwear. Given the poor condition of the roads boots were often worn, though here some clearly needed repairing. Minnie Scott in white, sitting on the ground at the front (on Eve Crawley's left), has 10 metal studs ('Blakeys') in her right boot but Minnie's left boot is in poor condition.

By contrast Joan Evans had a privileged childhood cared for by her Nannie. The following excerpt is from her autobiography 'Prelude and Fugue' and describes the state of the roads in about 1900 along with the advent of Spring and Summer.

'At least once a day, whatever the weather, Nannie and I sallied out for a walk; down our own bare and echoing flight, down the stuffy back stairs, past the vinous-smelling pantry and the secretive servants' hall, through a green baize door that shut with a mysterious clucking sound, past the warm kitchens and out by the back-door. Those were days before main roads were tarred or side roads macadamized; no one born since 1905 can realize the changes that new methods of road-making have brought to country life. For when I was a child, nor only were all roads, even the main road from London to Aylesbury, thick with white dust in summer, but all but the main roads were impassable to a child in a winter thaw, whether in a perambulator or on foot. The local road-metal disintegrated to a curious sticky mud, that could pull off a child's shoe or make pushing a perambulator as hard labour as a treadmill. So, unless there was a frost, our winter walk lay along the main road to King's Langley, for it was harder and drier than most. Generally we reached Vicarage corner, turned right about, and walked home again; or, if we felt we must see life, we went on through the village, past Mrs. Baldwin's', who sold everything, and especially Surprise Packets, in pennyworths, past Mrs Larter's the pastry cook's, and Mr. Spiegelhalter's the watchmaker's, as far as the Rose and Crown; and so home again.

Along that road, somewhere about 1900, we saw the first motor-car (impossible to abbreviate it !) that went from London to Aylesbury: a portentous thing that progressed jerkily forward, until, something went wrong and it backed violently into a heap of stones. The old roadmender, Nannie, and I looked at it in amazement, half realizing that here was something that would change our world. For in those days there was comparatively little traffic along the roads, - and except for a rare traction engine with a man holding a red flag walking in front, such as there was, was horse-drawn. Pedestrians were rather more numerous: tramps, pedlars, and gipsy women. I remember with pleasure a herbalist we would sometimes meet, looking for mandrakes in the roadside hedge between King's Langley and Hemel Hempstead: a medieval pilgrim straying along the road that was soon to become a modern highway.…............

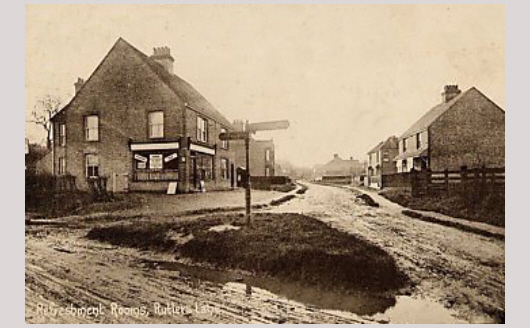

The coming of spring was every year a festival, consciously awaited. The tyranny of cold and darkness gradually weakened; the house woke up again to prepare for my parents' homecoming; the servants remembered their duties, and gradually, as the weather improved, we became free to walk in the lanes again. The first rite of spring was to go down Ruckler's Lane, over the half-dry ridges of the winter's mud, to get to the woods and look for the earliest primroses. Ruckler's Lane, indeed (it is now a suburban street of tiny villas), was then the road to Arcady. For a little later the woods it led to were misty with bluebells and foaming with wild cherry blossom; and then in June the long chalky slope to the south was starred with a tiny cystus, honey sweet. In June we would follow the lane, that smelled of dust and dog-roses, half-way to the woods, and then take to a field-path through the hay meadows. Here a few orchises grew, and every year we hunted for them, not to pick, but to admire. I think in those days I could have drawn a map of the field, with every unusual plant marked upon it; but I should have found it hard to name them, for Nannie, like most countrywomen, was no botanist, and her nomenclature did not go far beyond ham-and-eggs and star of Bethlehem. At the end of June the hay was cut, and the glory of the meadow departed. In the woods themselves a dense greenness and a fungus breath lay heavy on the air; and we spent more time in our own garden and went less far afield.'